In the mid-2000s, a large private collection of Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde appeared in Europe, consisting of hundreds of masterpieces - paintings by Lysytskyi, Rodchenko, Ekster, Honcharova and other masters.

It became known as the Sachs Collection after the owner, and works from it were sold in Europe for hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs.

Currently, works from the Zaks collection hang in two important American museums and one European one. One of them made it to recent Hollywood films, including Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer.

But experts say that the paintings may be fakes, and the story of the origin of the collection is a set of myths and fantasies.

While three art detectives investigated this legend of the lost grail of the Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde, BBC correspondents searched for its mysterious owner and those who helped him sell dubious paintings.

From Belarusian villages to Swiss auctions

In the early 2000s, an unknown private collector appeared in Minsk with good news: a huge collection of Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde paintings was found, and he wants to exhibit them in Belarus.

The collection contained more than two hundred paintings, including canvases by Lazar "Ely" Lysytsky, Oleksandr Rodchenko, Volodymyr Tatlin, Ilya Chashnyk, Nataliya Goncharova, Lyubov Popova, Oleksandra Ekster, Ivan Klyun, Robert Falk and other masters.

Its mysterious owner was the Soviet emigrant Leonid Zaks, now a citizen of Israel. He said that the unique collection was collected by his relatives, who received part of the masterpieces as a gift from Belarusian peasants, and the rest were bought either in Moscow or in Minsk thrift stores in the 1950s.

Belarusian cultural officials embraced the story with enthusiasm and organized several exhibitions.

But art critics were alarmed by the fact that Zaks carefully avoided the National Art Museum of Belarus, historical errors in his interviews, and finally the very quality of the paintings.

Vitebsk historian Oleksandr Lisov drew attention to the hoax: the catalog of one of the Belarusian exhibitions stated that the authenticity of the paintings was confirmed by "N. Seleznyova", employee of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. But there was never such an employee in the museum.

After that, exhibitions were no longer held in Belarus, and the article about the Zaks collection was removed from Wikipedia.

However, this did not stop the collector, but only changed the field of his activity. Exhibitions of the collection continued - but already in the private Swiss gallery Orlando in Zurich.

Between 2007 and 2014, there were at least five major exhibitions of the Zaks collection, and since it is a commercial gallery, all the paintings were available for sale.

Most of them were bought by private collectors - sometimes for hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs. For one family, these purchases caused family drama.

Art for the blind

When Rudolf Blum, the legendary Zurich collector, went blind in 2005, his work was carried on by his wife, Leonor. She began to actively buy works of art through the Zurich gallery Orlando, the owner of which was her acquaintance, Suzanne Orlando. Leonor Blum managed to buy dozens of paintings worth millions of Swiss francs.

Among them were the paintings of avant-garde artists of the first rank: Lysytskyi, Rodchenko, Popova, Tatlin, Ekster.

"My mother wanted to prove that she understood painting no worse than her father, and she believed Suzanne Orlando," recalls Beatrice Gimpel McNally, daughter of the Blums. - The father began to suspect something bad, but what could he do?".

By the time Leonor Blum started buying these paintings, she had already been diagnosed with vascular dementia. But when Beatrice shared her doubts with her mother, she was very angry with her.

These pictures forever ruined their relationship.

However, Beatrice's suspicions were justified. After the death of her parents, estate appraisers said the paintings in the Zaks collection were worthless. Auction houses in London refused to consider them, but in one of them she was advised to turn to James Butterwick, a British dealer and connoisseur of the Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde.

"Derussification" of the avant-garde

Until recently, the works of artists created in the first quarter of the 20th century in the territory of the former Soviet Union were called "Russian avant-garde", and this concept included such currents as Suprematism, Constructivism, Promenism, Cubofuturism, etc. Now this term is considered inappropriate, imperialistic and colonial. Alternative definitions are increasingly used, for example, "Ukrainian" and "Soviet" avant-garde.

In 2022, after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the word "Russian" also disappeared from the name of the James Butterwick gallery - instead, it is said that the gallery is dedicated to "Ukrainian and European art".

Butterwick became interested in avant-garde art after a student exchange in the USSR, after which he even moved to live in Moscow for a while.

Then, in the 1990s, with the advent of the market economy, the art market came out of the underground and was flooded with fakes. But it was not about the mass production of fakes, but rather about an uncritical attitude to old things.

Everything changed in the 2000s, when Russian capital went to the West. In December 2004, over a thousand paintings by Russian and Ukrainian masters were presented at two London auctions. And they were mostly bought by Russians.

In November 2008, at the height of the global economic crisis, Malevich's "Suprematist composition" sold at a New York auction for a record $60 million. Ten years later, the same picture will be sold for 86 million.

The skyrocketing prices have given rise to an industry of producing and servicing entire fake collections, experts say.

Soon, police raids in Europe will begin to find warehouses with hundreds and sometimes thousands of paintings of unknown origin.

Butterwick also began to notice that more and more of the dubious paintings customers showed him were accompanied by articles and expert opinions.

Such papers were also accompanied by paintings, with which the Blums' daughter Beatrice turned to him.

James decided to look into this story together with his friends, Ukrainian art critic and curator Kostyantyn Akinsha and St. Petersburg collector Andrii Vasiliev.

Akinsha, who specializes in provenance, that is, the history of the origin of works of art, offered to understand the incredible history of the collection.

"Working on fakes"

According to Leonid Zaks, the founder of the collection was his grandfather Zalman, a merchant from the then Katerynoslav (now the city of Dnipro). Zalman allegedly became interested in radical art after seeing it in the Belgian bank of Katerynoslav, and began to buy paintings.

Anna (Nehama) Sachs, who was a military medic, continued her father's work. In 1944–1945, she treated Belarusian peasants, who brought her paintings by Lysytskyi and Ekster in gratitude for her work.

And the final contribution to the future collection was made by Anna's brother Moisei, who disappeared in 1941 at the front, and in the 1950s appeared in Moscow already as an American businessman.

At that time, the works of avant-garde artists were condemned as "formalist art" and sold to thrift stores.

According to family tradition, Moses Zaks bought several dozen of these masterpieces in 1955-1956 and took them to Europe. They lay there until the 1990s, when the collection was inherited by his nephew, an oilman from Moscow named Leonid Zaks, who told these fascinating stories about his relatives.

As evidence, Zaks provided buyers with a 2008 letter from the National Museum of History and Culture of Belarus, which details the entire story – but with significant contradictions, strange errors and misprints.

In response to Vasiliev's request, the museum reported that no such letter was found in the archive.

"That is, by all parameters, this letter is fake," the collector concludes.

But the art detectives did not stop there. They conducted research in Russian and Belarusian archives, wrote dozens of requests to museums and checked all the key facts of this story.

"We have checked the entire provenance of the Zaks collection, and every element of this provenance is not supported by anything, rather we are able to disprove it. Before us is a classic Provençal myth," says Akinsha.

In museums and Hollywood movies

PHOTO BY UNIVERSAL PICTURES Image caption Cillian Murphy's Oppenheimer looks at a painting from the Zaks collection attributed to Ivan Clune

Two works from the Zaks collection are housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Ukrainian artist Oleksandra Ekster was called the author of the first one, and Ivan Klyun was the author of the second one - "Hodynnykar".

It was "The Watchmaker" that was included in two films of 2023 - in "Oppenheimer" by Chris Nolan and in "The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar" by Wes Anderson.

The BBC contacted the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and informed them of the verification of the provenance of the Zaks collection. The museum promised to conduct its own investigation.

Shortly after our letter, the picture was removed from the exhibition, and the signature to it on the website of the institute changed. Now it is listed as "attributed to Ivan Klyun".

Another canvas from the Zaks collection, attributed to the Ukrainian avant-garde artist Oleksandra Ekster, is kept in the Cleveland Museum of Art. The curators of the museum were interested in the results of the BBC investigation, but refused to comment.

We discovered that another work from the Sachs collection is in the world-famous Albertina Gallery in Vienna. It was called "Genoa" and it was also attributed to the avant-garde Exeter.

Speaking to the BBC, representatives of the museum said that they had carried out their own checks on the painting and that it was not on display.

Flat screen TV in the interior of the 18th century.

Beatrice gave the BBC two paintings from the Zaks collection - El Lysytskyi's "Proun" and Lyubov Popova's "Picturesque Architecture".

We brought them from Zurich to the Art Discovery laboratory in London, where they were analyzed by Jillin Nadolny, a leading scientist in the field of technical and technological analysis of painting, who debunked dozens of fakes of the "Russian" avant-garde.

Her analysis revealed in the painting by Lysytskyi, who died in 1941, fibers frozen deep in the paint, which were treated with substances that became widely available only after the Second World War.

"It's like a painting from the 18th century, in which a flat-screen TV can be seen in the background. It is impossible. This cannot be. It doesn't happen that way," she said.

The painting is a forgery, Nadolny wrote in her conclusion. She came to the same conclusion regarding the painting attributed to Popova.

The BBC also tracked down those who helped Zacks build a reputation for the collection - and wrote articles that the Orlando gallery issued to Beatrice's parents to convince them of the authenticity of the paintings being sold.

Anton Uspenskyi, a leading researcher at the Russian Museum, is the only living art critic associated with the famous museum who spoke positively about the Zaks collection. He published three articles about the collection, including in prestigious magazines.

But in a conversation with the BBC, he said that he did not check this information himself and wrote everything from the words of Zaks: "These are family memories that are not confirmed in any way, not recorded anywhere."

He also noted that he did not confirm the authenticity of the paintings - and even never saw any work, only photographs. He said he was unaware of his name being used in the sale.

In the articles, Ouspenskyi also claimed that another "Proun" by Lysytskyi from the Zaks collection was bought by the Basel Art Museum - but this is not true.

"As a result of intensive research in our archives, we have not found any traces of the Sachs family in general or works related to them in particular," the head of the provenance research department of the Basel Museum told the BBC.

Vitebsk-based art critic Tetyana Kotovych also wrote a lot of praise about the Zaks collection.

"This is news to me. What you are talking about is using my name. There is no statement anywhere that I guarantee that this is the artist," she said when asked by the BBC about the role of her articles in the sale of paintings.

Kotovych wrote that "Zachs fruitfully cooperates with the most distinguished experts", and listed the members of the association of experts of the "Russian" avant-garde InCoRM, who issued certificates for many works from the collection, which were sold in the Orlando gallery.

Shortly thereafter, InCoRM found itself at the center of two scandals when its members' credentials surfaced in high-profile Russian avant-garde forgery trials in Germany and Belgium.

Patricia Railing, the founder and president of InCoRM, told the BBC that the organization collapsed due to attacks by critics: "With all these allegations of forgery and slander, no one wanted to be associated anymore...".

"Who should I believe - strangers or my mother?"

PHOTO AUTHOR, KP

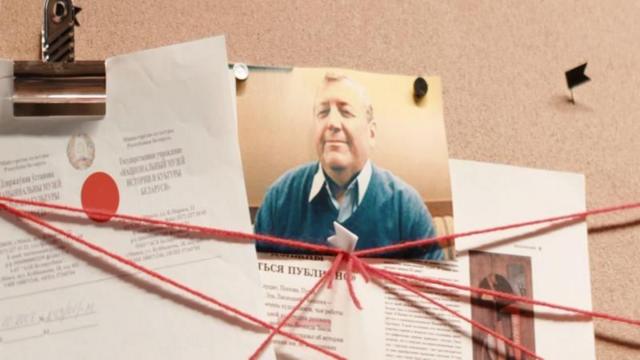

All this time, the BBC also tried to talk to Leonid Zaks himself. We wrote and called him at all possible addresses and numbers. His daughter forwarded our inquiry to him, but even then Zachs did not respond.

And only two weeks before the release of our investigation, he got in touch and suddenly agreed to a telephone interview.

What happens to the part of his collection that he did not manage to sell and where is it now? Zaks evaded the answer: "I would like to avoid this question and some others... price and others... It is stored, this collection, in a European warehouse."

He refused any responsibility for paintings sold on the European market.

"I was detached from these paintings from the moment they left the Orlando gallery. I think that these questions should not be addressed to me!".

Every time he repeated: "I didn't sell anything."

Then we asked him to tell us about the provenance of the collection. How can he confirm the stories about the peasants who distributed modernist masterpieces in 1944-1945?

"And what evidence? Can you imagine what was there after the war?” Zaks answered.

In response to the experts' conclusions, the collector said that the history of the collection was written down by his mother, an "honest person", and added: "Well, who should I believe - people I don't know or my mother?".

Zaks was also surprised by the amounts that Beatrice's parents paid for works from his collection. He claimed that his works could not be worth hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs - and called such sums delusional.

"I have never seen such money from the Orlando gallery," he said.

Zaks was also offended that Anton Uspenskyi told the BBC that he had not seen the paintings and was not involved in their sale.

"Ouspensky visited the Orlando gallery, and more than once, by the way. And he saw what kind of gallery it was, how it worked. He knew it was a commercial gallery like a store," Zaks insisted.

At the end of the call, we asked Zaks if he wanted to apologize to Beatrice.

"I cannot apologize, but I can sympathize. There is nothing to apologize for," he replied.

"A wave of fakes flooded the whole world"

Deceived collectors of expensive paintings rarely evoke sympathy. After all, these are rich people with extra money.

But in the case of Malevich, Lysytskyi, Ekster, Popova, Goncharova and other avant-garde masters, it has long been not just a question of the loss of private buyers, but a threat to their entire heritage.

"There are much more fakes than real things," says Andriy Vasiliev.

The history of the Zaks collection shows how easily dubious paintings with fabricated stories can find their way into the world's leading museums. There they are seen by hundreds of thousands of people, they end up on the pages of textbooks, and a new generation of art critics learns from them.

It was the sending of fakes that forced Akinsha, Vasiliev and Butterwick to fight against fakes. But sometimes even they despair - and assume that the outcome of this battle is already known.

"With the help of numerous art historians who consider themselves academic scientists and at the same time generously issue certificates to confirm the authenticity of dubious works, the avant-garde has turned into a giant room of crooked mirrors inhabited by monstrous twins," Akinsha wrote in one of his articles.

With many losses, the creativity of the radical experimenters of that era - Ukrainian, Russian, Jewish artists - nevertheless managed to survive the persecution of the Soviet authorities, the Second World War and the Iron Curtain.

But decades of market booms and the resulting wave of fakes threaten to bury their legacy under mountains of bad copies.