Високосні роки здавна мають погану славу: від них чекають неприємностей, хвороб, смертей і навіть землетрусів, повеней та воєн. Але що таке взагалі високосний рік і звідки він узявся?

Як і багато в житті, високосний рік прийшов до нас зі Стародавнього Риму.

З середини VIII століття до н. е. у Римі користувались календарем, що мав 10 місяців, а рік тривав 304 дні. У VII столітті до н. е. правитель Нума Помпілій провів реформу, додавши до календаря ще два місяці, і рік “виріс” до 355 діб.

Однак за часів правління Юлія Цезаря римський календар був хаотичним.

Рік мав 355 днів, що ділилися на 12 місяців, прив’язаних до місячних циклів. Однак місячний рік не збігається з сонячним, тому римляни вигадали тринадцятий місяць року і назвали його мерцедоній – на честь богині-покровительки товарообміну і платежів.

Мерцедоній з’являвся у календарі раз на два роки – за сучасним рахунком після 23 лютого.

Він міг мати 22 або 23 дні, тому тривалість року коливалася від 355 до 378.

Якоїсь миті з’ясувалося, що календар містить помилку, яка призводить до часового спотворення. Тоді право оголошувати мерцедоній передали великому жерцю-понтифіку, що мав вносити корективи залежно від серйозності спотворення.

Однак жерці-понтифіки почали використовувати своє право в політичних цілях, скорочуючи період правління одних консулів та збільшуючи термін повноважень інших.

Виправити ситуацію вирішив верховний правитель Риму Юлій Цезар.

Зайнявшись цією проблемою, він жахнувся. Через усі ці зміни римський календар відхилився від природних реалій більш як на два місяці. І така різниця завдавала шкоди насамперед сільському господарству, оскільки святкування врожаю припадало на середину весни, коли до самого врожаю було ще далеко.

Цезар запросив до Риму Созігена Александрійського — найшанованішого математика й астронома I століття до нашої ери.

Созіген запропонував взяти за основу єгипетський сонячний календар, створений за кілька тисячоліть до цього.

Але перш ніж запровадити новий календар, потрібно було усунути помилки старого. Усі “втрачені” понтифіками дні вставили між листопадом і груднем. В результаті 46 рік до н. е. вийшов найдовшим за всю історію людства — він складався з 445 днів, розбитих на 15 місяців.

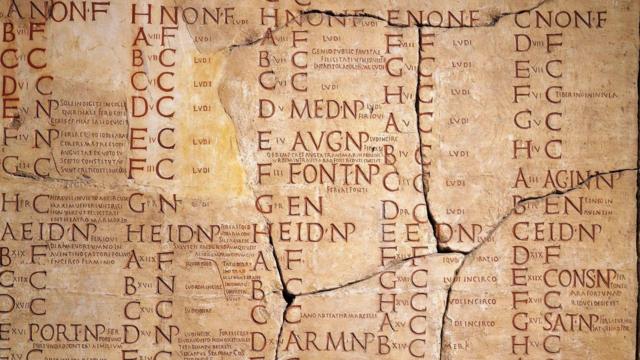

АВТОР ФОТО,GETTY IMAGES Підпис до фото, Сільськогосподарські заходи та релігійні свята були тісно пов’язані у римську епоху, але їх було важко відстежувати без надійного календаря

З січня 45 року до н.е. Рим почав жити за новим календарем.

Згодом його запозичили інші країни західного світу. Назву “юліанський” календар отримав вже після смерті Юлія Цезаря.

Чому рік назвали “високосним”?

В юліанському календарі додатковий день у високосні роки ставили не на кінець лютого, як це робиться зараз, а між 23 та 24 числом. Називали його bis sextum Kalendas Martium – “двічі шостий до березневих календ” (календи – це перше число кожного місяця). А рік тривалістю 366 днів називали annus bissextus.

При цьому початок року Цезар переніс на 1 січня.

АВТОР ФОТО,GETTY IMAGES Підпис до фото, Римські свята та інші важливі дати підпорядковувались примхам календаря, який змінювався з року в рік непередбачуваним чином

Інші календарні реформи

Йшов час, і ставало дедалі очевидніше, що у розрахунки вкралася помилка – римські жерці оголошували високосним не кожен четвертий, а кожен третій рік.

Ситуацію виправив імператор Октавіан Август.

В подяку за це римський Сенат у VIII році до н. е. перейменував місяць Sextilis на Augustus (серпень). А сам місяць отримав 31-й день, який взяли з кінця лютого. Таким чином лютий вкоротився й став тривати 28 днів звичайного року й 29 високосного.

АВТОР ФОТО,GETTY IMAGES Підпис до фото, Навіть невелика різниця між календарем і рухом Землі навколо Сонця призводить до появи розбіжностей

1582 року до календарної реформи долучився папа римський Григорій XIII. Він створив спеціальну комісію, до складу якої увійшли не лише священнослужителі, а й астрономи.

Того ж року Григорій XIII оголосив про створення нового календаря, який ми зараз знаємо як григоріанський. Він містив кілька значних змін. Перше — рахунок днів пересунули на 10 діб уперед: після 4 жовтня настало одразу 15-те. Оскільки католицька церква прийняла юліанський календар лише у 325 році н.е., за 12 з половиною століть набігла різниця у 10 днів. Тому до кінця XVI століття день весняного рівнодення “сповз” з 21 березня на 11-те. Рішення ж Григорія XIII дозволило вже 1583 року повернути його на 21 березня.

Як і в юліанському календарі, високосними у григоріанському стали роки, порядкові номери яких повністю діляться на 4 (наприклад, 2024-й). Але, крім цього, він закріпив нове правило: відтепер рік, порядковий номер якого ділиться на 100, але при цьому не ділиться на 400, не вважається високосним.

Наприклад, 1600 і 2000 роки – високосні, а 1700, 1800, 1900 та 2100 – ні.

Поступово зникала звичка подвоювати у високосному році 24 лютого, як це робили у Стародавньому Римі. Натомість раз на чотири роки в календарях почала з’являтися нова дата — 29 лютого.

Григоріанський календар набув поширення та синхронізувався на міжнародному рівні, але і він, на жаль, не є ідеальним.